Geometric Amoebot Model

AmoebotSim 2.0 is a simulation environment for the geometric amoebot model with its reconfigurable circuits and joint movement extensions. The purpose of the simulator is to provide a platform for algorithm developers to implement and run their amoebot algorithms, allowing them to see the algorithms in action and test them in arbitrary scenarios. In order to develop such algorithms, a good understanding of the underlying amoebot model is required. This and the following pages provide formal descriptions of the basic model and its extensions implemented by the simulator.

Model Description

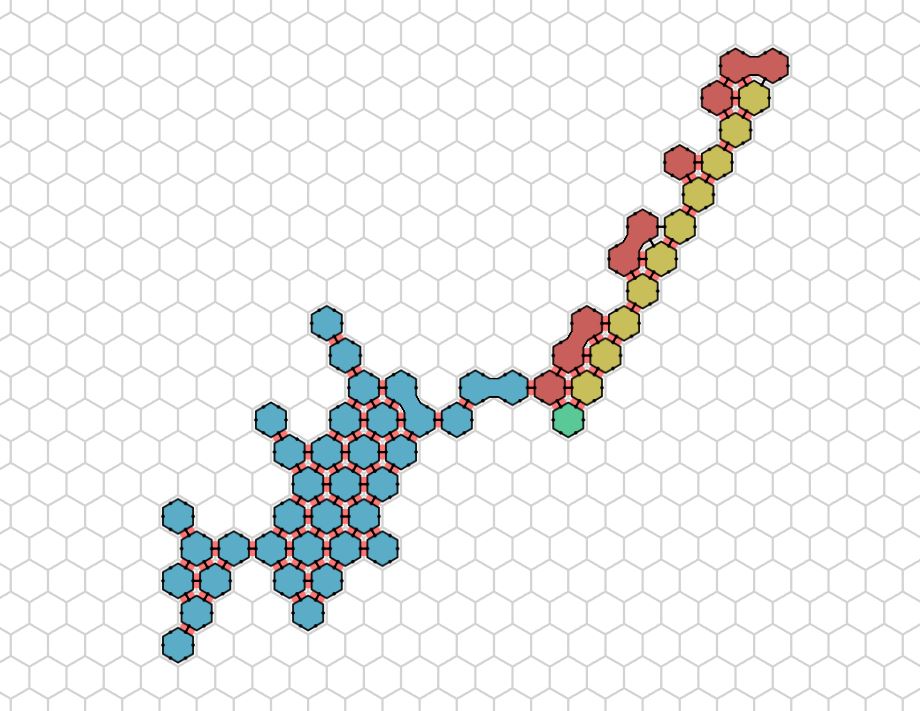

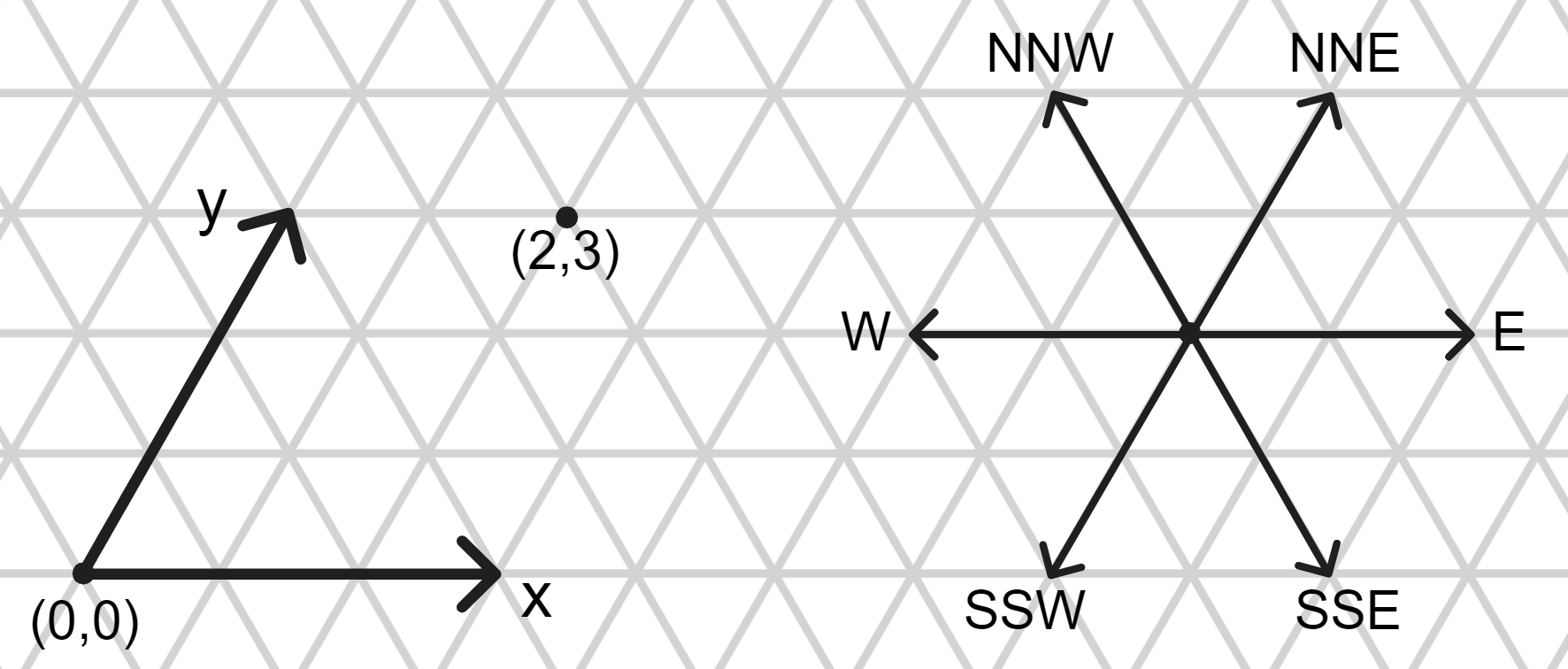

In the geometric amoebot model, the two-dimensional world is represented by the infinite regular triangular grid graph \(G_\Delta = (V,E)\) (see image below). In this graph, each node has exactly six neighbors, spread evenly around the node at unit distance. Its structure induces six cardinal directions on three axes, two of which we use to define a coordinate system on the grid. In the image below, the E-W axis and the NNE-SSW axis define the coordinates.

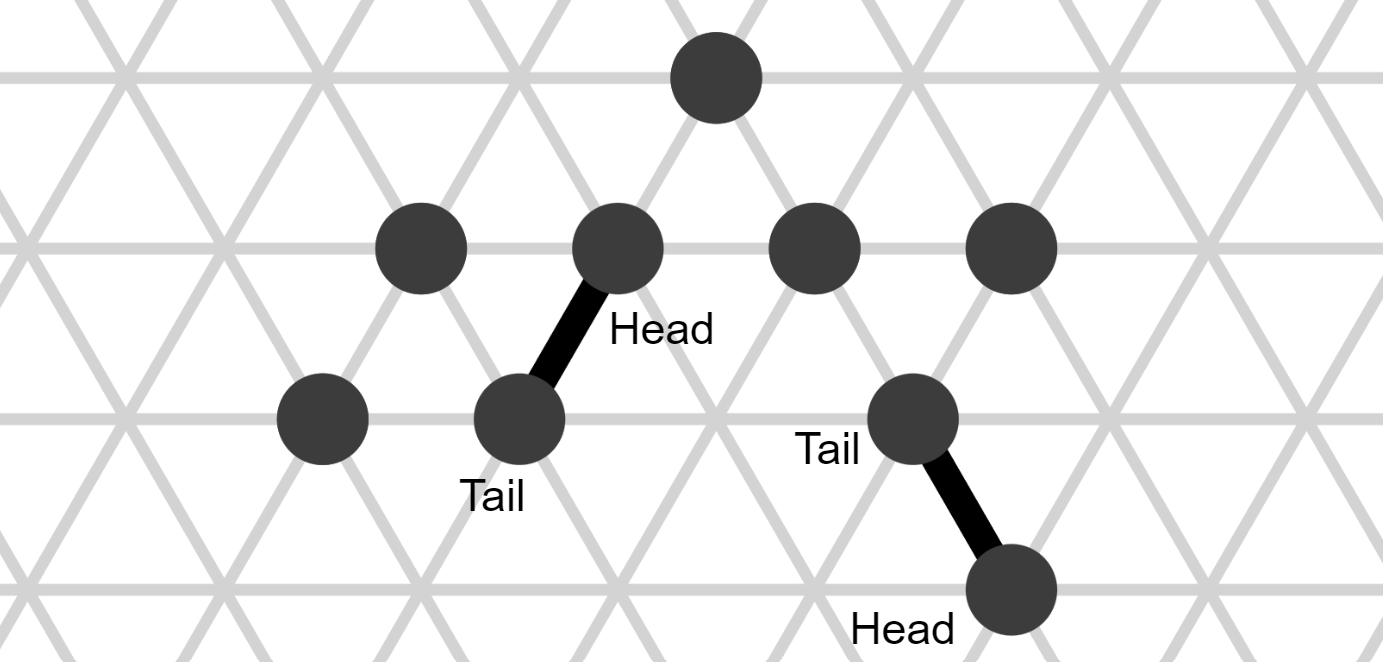

An amoebot particle (short "amoebot" or "particle") is an anonymous, randomized finite state machine that occupies either one or two adjacent nodes of \(G_\Delta\) at all times. Each node of the graph can only be occupied by at most one amoebot at a time. An amoebot that occupies one node is called contracted and an amoebot occupying two nodes is called expanded. If an amoebot is expanded, exactly one of its two occupied nodes is called its head and the other occupied node is called its tail. For a contracted amoebot, its head and tail are the same node. Amoebots occupying adjacent nodes of \(G_\Delta\) are called neighbors.

Note

Throughout this documentation, we use the terms amoebot and particle interchangeably. The term "particle" is used more in the program code due to the naming practices when the simulator was first created.

Let \(S \subset V\) be the set of grid nodes occupied by amoebots. We say that the amoebot structure is connected if the subgraph \(G(S)\) induced by \(S\) is connected. In the model version implemented in the simulator, we demand that the initial amoebot configuration is connected and remains connected throughout the whole simulation.

Movements

Amoebots can move through contractions and expansions. A contracted amoebot occupying a node \(v \in V\) can expand to any of the up to six unoccupied nodes adjacent to \(v\). After the expansion, the amoebot is expanded and occupies both \(v\) and the adjacent unoccupied node \(u\) in the expansion direction, with \(u\) being the amoebot's head and \(v\) being its tail.

Conversely, an expanded amoebot occupying nodes \(u, v \in V\) can contract into \(u\) or into \(v\). After the contraction, the amoebot is contracted and occupies only one of the two nodes. We distinguish between the two possible movements by saying that the amoebot contracts into its tail or into its head.

There is also the special handover movement which allows a contracted and an expanded amoebot to expand to and contract from the same node in a single movement. More precisely, let the contracted amoebot \(p\) occupy node \(u \in V\) and let the expanded amoebot \(q\) occupy \(v, w \in V\) such that \(u\) and \(v\) are adjacent. Then, \(p\) can perform a push handover to expand onto \(v\) while \(q\) performs a pull handover, contracting into \(w\). The two amoebots must agree by both actively performing this movement.

The animation above shows the three types of movements: The amoebot on the left expands in the NNE direction, while the amoebot in the middle contracts (it could be either its head or its tail). The two amoebots on the right perform a handover movement.

While all amoebots are identical in terms of their abilities, they may view the world from different perspectives: Each amoebot has a compass orientation defining which of the six (global) cardinal directions it perceives as the East direction. For example, if an amoebot's compass direction is West, then its sense of direction is the exact opposite of the global directions. Additionally, each amoebot has a chirality, meaning a sense of rotation. The "default" global chirality is counter-clockwise, i.e., the positive rotation direction is counter-clockwise and directions are traversed in the order E, NNE, NNW, W, etc. If an amoebot has inverse chirality, its positive rotation direction corresponds to the global clockwise rotation direction (also called clockwise chirality). Imagine two clocks laid down on a table, one facing up and one facing down: From each clock's perspective, it is ticking in the same (clockwise) direction, but when looking at the table from above, the clock facing down is ticking the opposite way.

The amoebots do not know their own compass direction and chirality, and initially, they might not agree with each other. However, there are algorithms for establishing a common compass direction and chirality. Thus, some algorithms simply assume that all amoebots have the same compass direction and chirality from the start.

Activations

We assume the fully synchronous activation model. This means that a computation proceeds in discrete rounds and in each round, every amoebot is active exactly once. Furthermore, all activations occur simultaneously and their consequences only take effect when the round is over. When an amoebot is activated, it can alter its internal state and perform actions (such as movements) as a function of its current state and its surroundings. The state of an amoebot is the combination of its internal state variables (called attributes) and its current expansion state (including the expansion direction if it is expanded). An amoebot can only perceive its own state and the states of its direct neighbors. It is oblivious to anything happening beyond this range. When a round starts, each amoebot takes a snapshot of its own state and surroundings, which it then uses to compute its next state and its actions. It is important to emphasize that each amoebot takes its snapshot before any state changes are performed by any other amoebot. The runtime complexity of an algorithm is measured by the number of rounds it takes to complete.

The activation model has potential for conflicts, such as two amoebots trying to expand onto the same node in the same round. In some models, these conflicts are resolved by letting an adversary decide which amoebot gets to perform its movement. In the simulator, however, such conflicts are not allowed and the round simulation will be aborted if a conflict occurs.

We refer to the following papers for more information on the basic geometric amoebot model:

- Amoebot - a New Model for Programmable Matter by Derakhshandeh, Dolev, Gmyr, Richa, Scheideler and Strothmann (ACM, 2014) for the initial proposal and the original description of the amoebot model

- The Canonical Amoebot Model: Algorithms and Concurrency Control by Daymude, Richa and Scheideler (Schloss Dagstuhl, Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, 2021) for a more recent, generalized model unifying the notation for the different versions and assumptions of the amoebot model

Continue reading about the model's extensions implemented in the simulator:

Refer to the Model Reference pages for more information on how the model is implemented and used in the simulator.